The South Florida Canal System

In the late 1940s, South Florida was hit by a series of hurricanes that flooded the area, leading to significant damage and loss of life. As a result, in 1950, the state launched the Central and South Florida Flood Control Project, building a system of 1,800 miles of canals, hundreds of flood gates and pump stations designed to re-channel flood waters. “They designed it so agriculture and urban development would be protected,” says Carlos Adorisio, P.E. CFM Engineering Unit Supervisor, Environmental Protection and Growth Management Department.

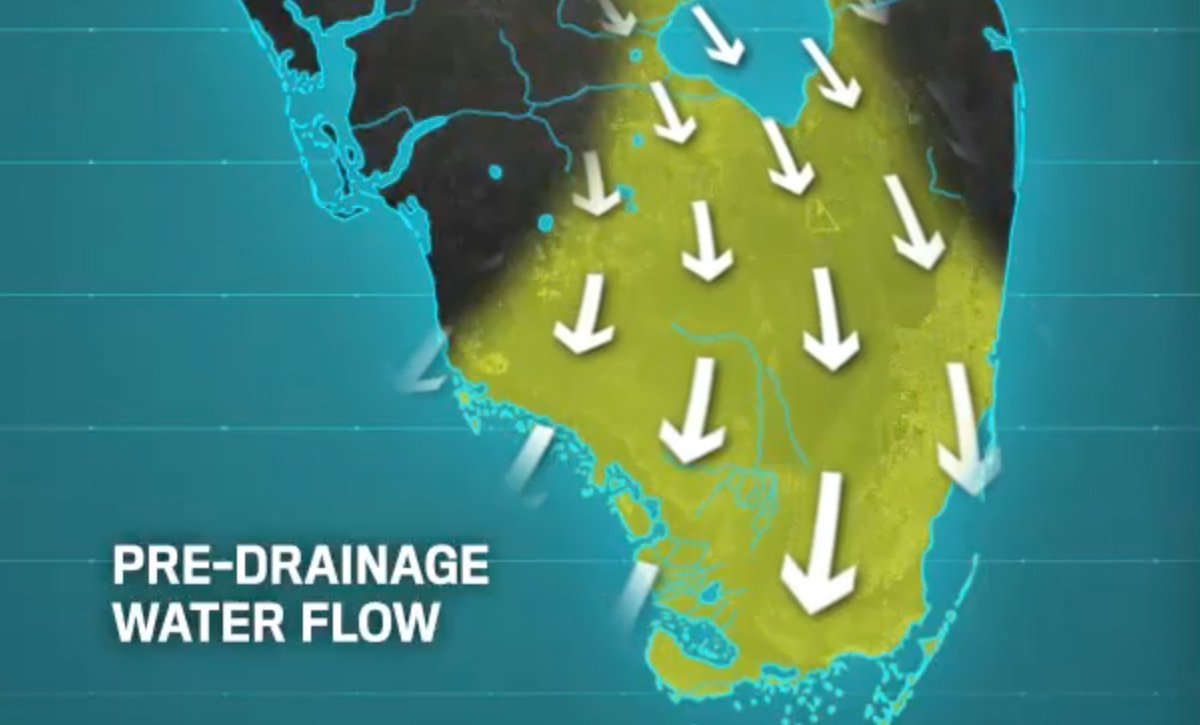

Before the Project, overflow from the Kissimmee River, a 90-mile slow moving, meandering river that flowed through the middle of central Florida, ran south and fed fresh water to the Everglades.

After the Project, the river was channelized and straightened, shortening it to 50 miles. Now, instead of moving south to supply the Everglades with fresh water, most of the water moves to the estuaries. And when it does move south, it moves through canals. What used to be a slow-moving river is now a closely managed system of canals designed to control the flow of water through the region.

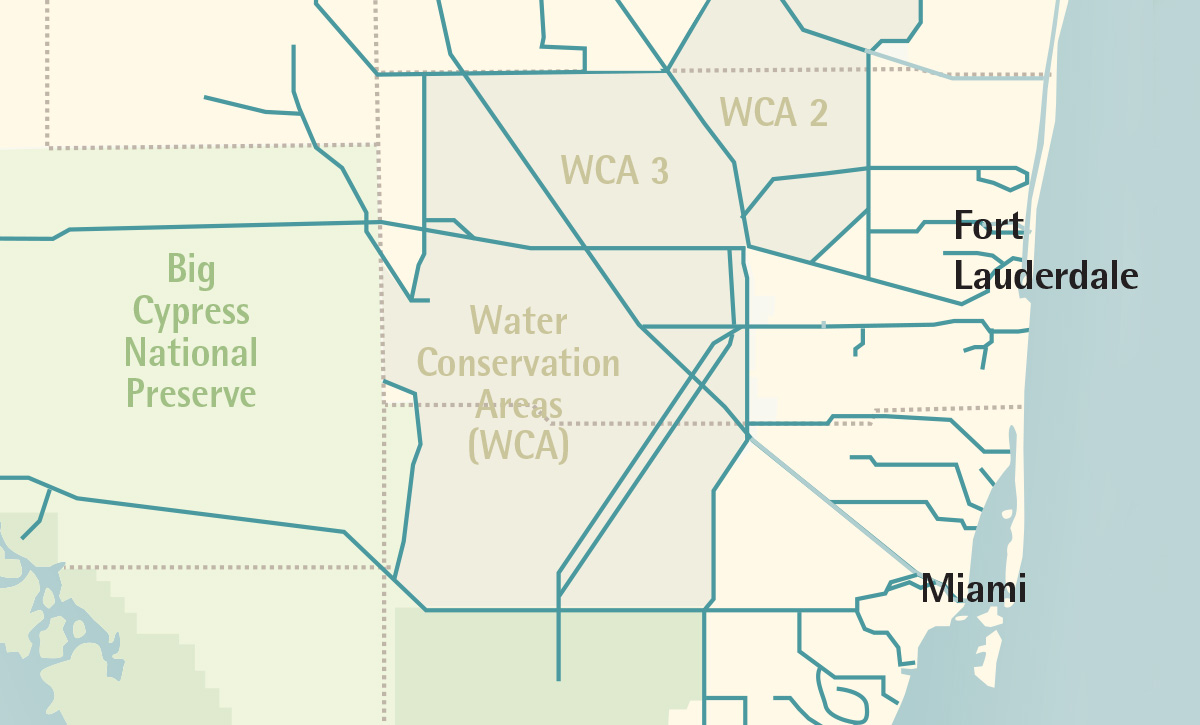

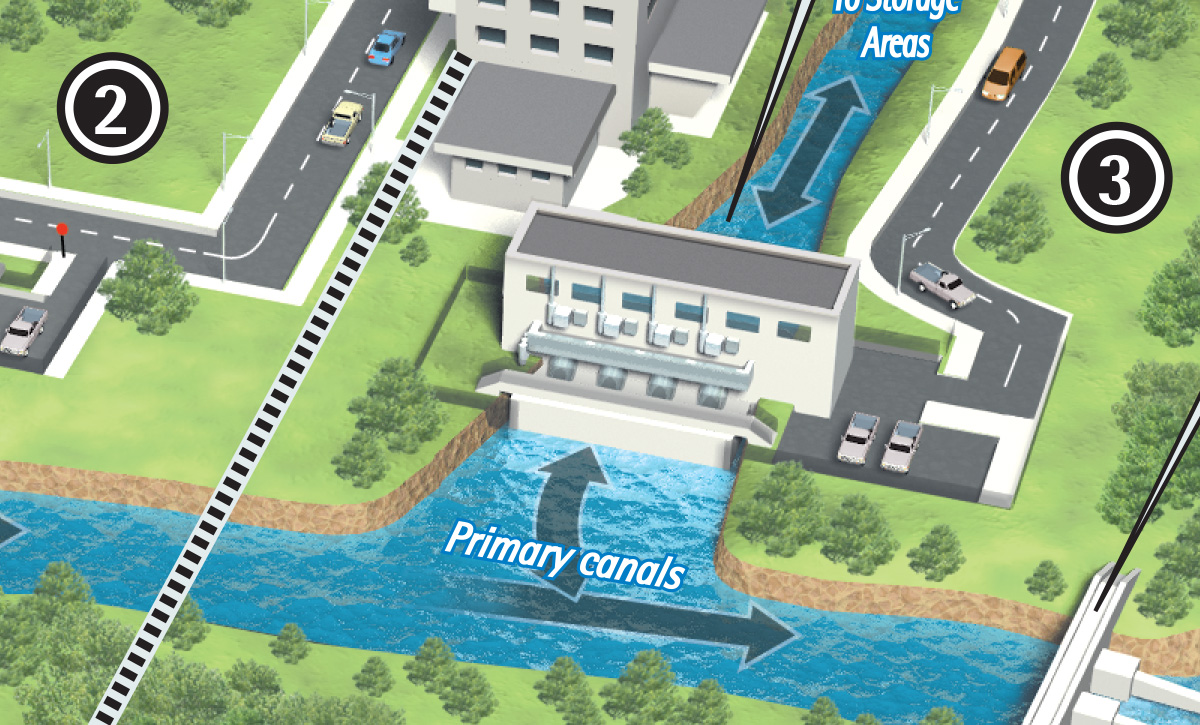

The canals are managed by the South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD), which was created at the time of the Project and given stewardship over water quality, environmental protection and flood prevention. SFWMD manages Broward County’s primary canals—seven large, main canals running east to west and three north to south. When there is excess water—for example after a rain storm—water is moved through the canals out to the ocean or into the Everglades. During the dry season, when water is needed in South Florida, is it moved from Lake Okeechobee through the primary canals.

The primary canals are fed by a secondary system comprised of smaller canals. These are managed by local drainage districts or municipalities. Finally, the secondary canals connect to a tertiary system—essentially storm water management systems on individual properties or within neighborhoods--which drain into the ground water, feeding the aquifer. These systems rely on a combination of storm drains, culverts, swales, exfiltration trenches, retention areas, drainage wells, lakes and wetlands to collect, convey, and absorb storm water.

How Water Moves through the Canal System

During the dry season, November to April, because the land has not received significant rainfall, the ground water goes down. At the same time, the population in Broward County swells as tourists flock to the area, increasing demand for water. South Florida takes water from Lake Okeechobee, the conservation area, and moves it down through the primary canals to the secondary system to keep the water level in the canals high. This is so the water in the canals moves into the ground water. Conversely, the canals are kept lower in the wet season when the ground water is high.

Whenever a storm is forecast, SFWMD begins to reduce the water level in the canals, moving water through the canal system either to the conservation area or to the ocean, giving them a head start on the storm. During the storm, when the water starts running off, it fills the canals again.

Significant sea level rise will affect the entire system—especially in the wet season—because the ground water will start at a higher elevation. The system relies on gravity—rather than pumps—to move the water—because of the high energy costs associated with running pumps. But gravity doesn’t always work well enough to move the water, resulting in flooding.

Drainage wells

Drainage wells were most often used on properties with no room for retention lakes or other drainage devices. “When a property is very valuable, they try to use as much as possible [for development]. When the percentage of impervious ground is very high, upwards of 80% of the property, developers will install a system to treat the water through filtration trenches, and then they drain the water into drainage wells. Many properties could not be developed unless they have those wells,” explains Adorisio.

Drainage wells consisted of vertical iron pipes sunk between 50 and 160 feet into the ground to reach the lip of a well dug 10 to 20 feet deeper. At that depth, the ground is comprised of hard but very porous limestone so as water drains into the well, it disburses quickly into the aquifer. “You can move substantial amounts of water into the ground this way,” says Adorisio, noting that while runoff from roofs could drain directly into drainage wells, water from a parking lot, lawns, etc. first needs to be treated “so only clean water gets into the well,” says Adorisio. A 100-acre commercial center, for instance, would support 28 drainage wells; smaller developments with ten homes might share a single well.

In neighborhoods suffering drainage problems, municipalities often elect to build drainage wells. “Some cities have decided as a neighborhood improvement plan they are going to dig drainage wells that will receive water from an entire neighborhood,” says Adorisio.

While new developments provide their own drainage, older neighborhoods did not. “In the old neighborhood in the fifties, the developers just came in and built. Nobody was thinking at the time about drainage,” says Adorisio.